China Will Crush Us

-

Latest Rankings

-

Updated

-

Updated

-

Updated

-

Updated

-

-

College Commitments

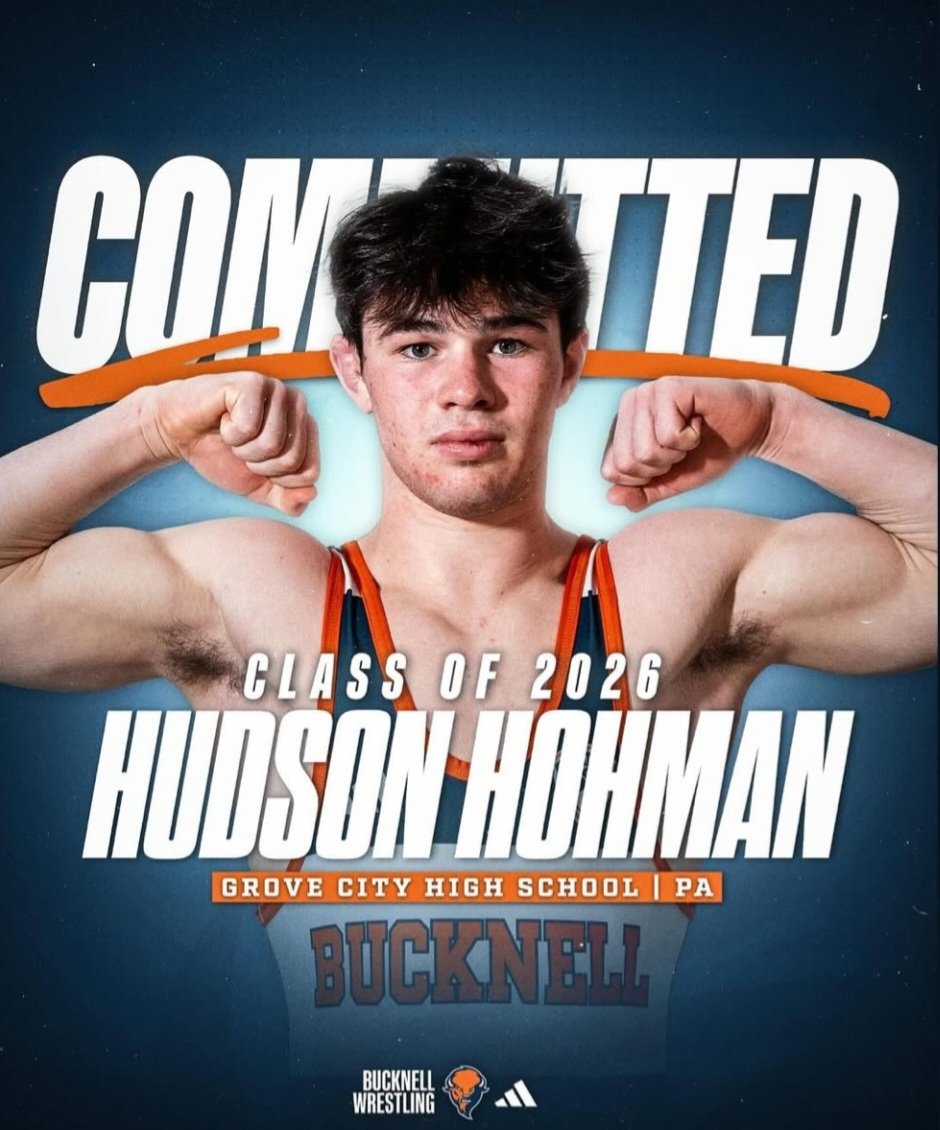

Hudson Hohman

Grove City, Pennsylvania

Class of 2026

Committed to Bucknell

Projected Weight: 157

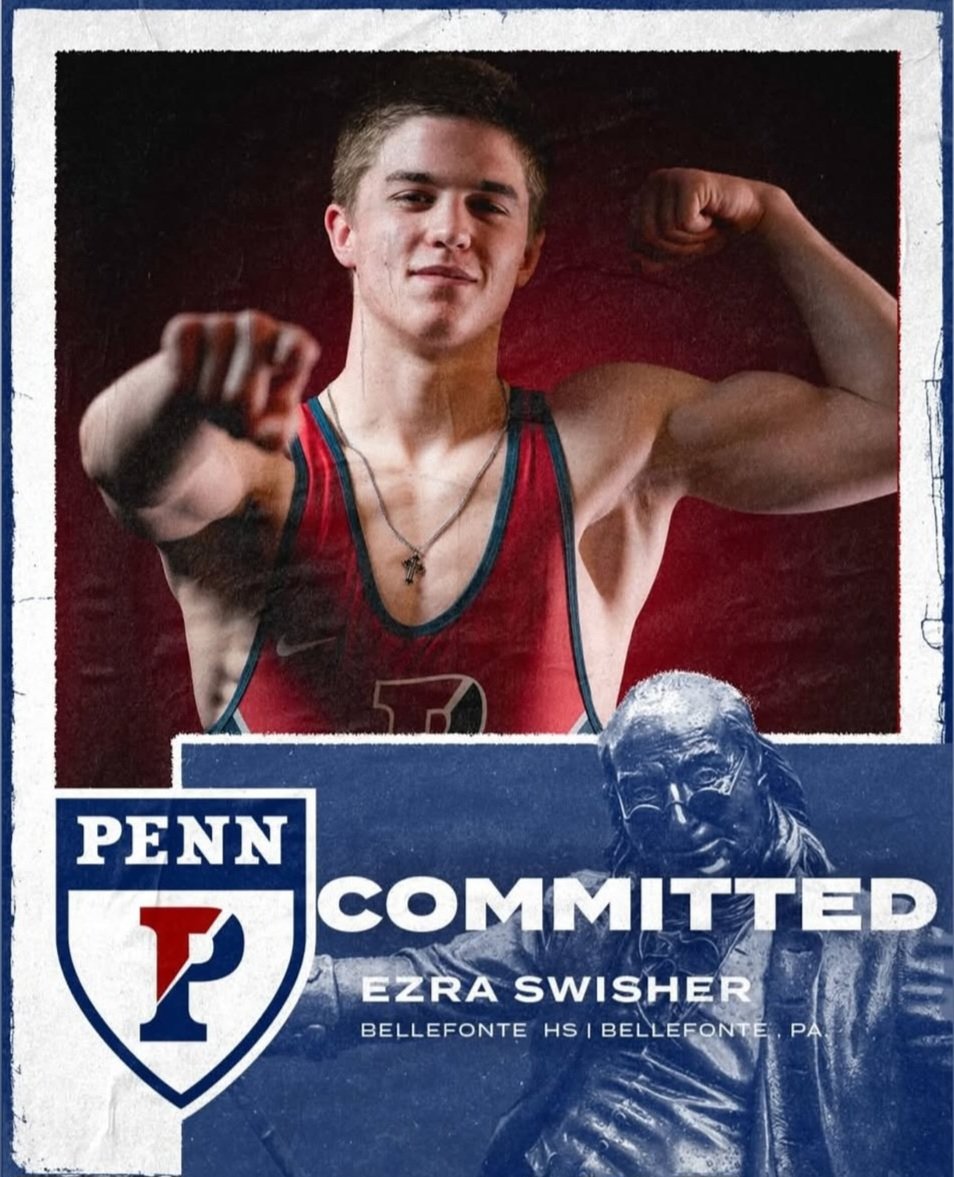

Ezra Swisher

Bellefonte, Pennsylvania

Class of 2026

Committed to Penn

Projected Weight: 157

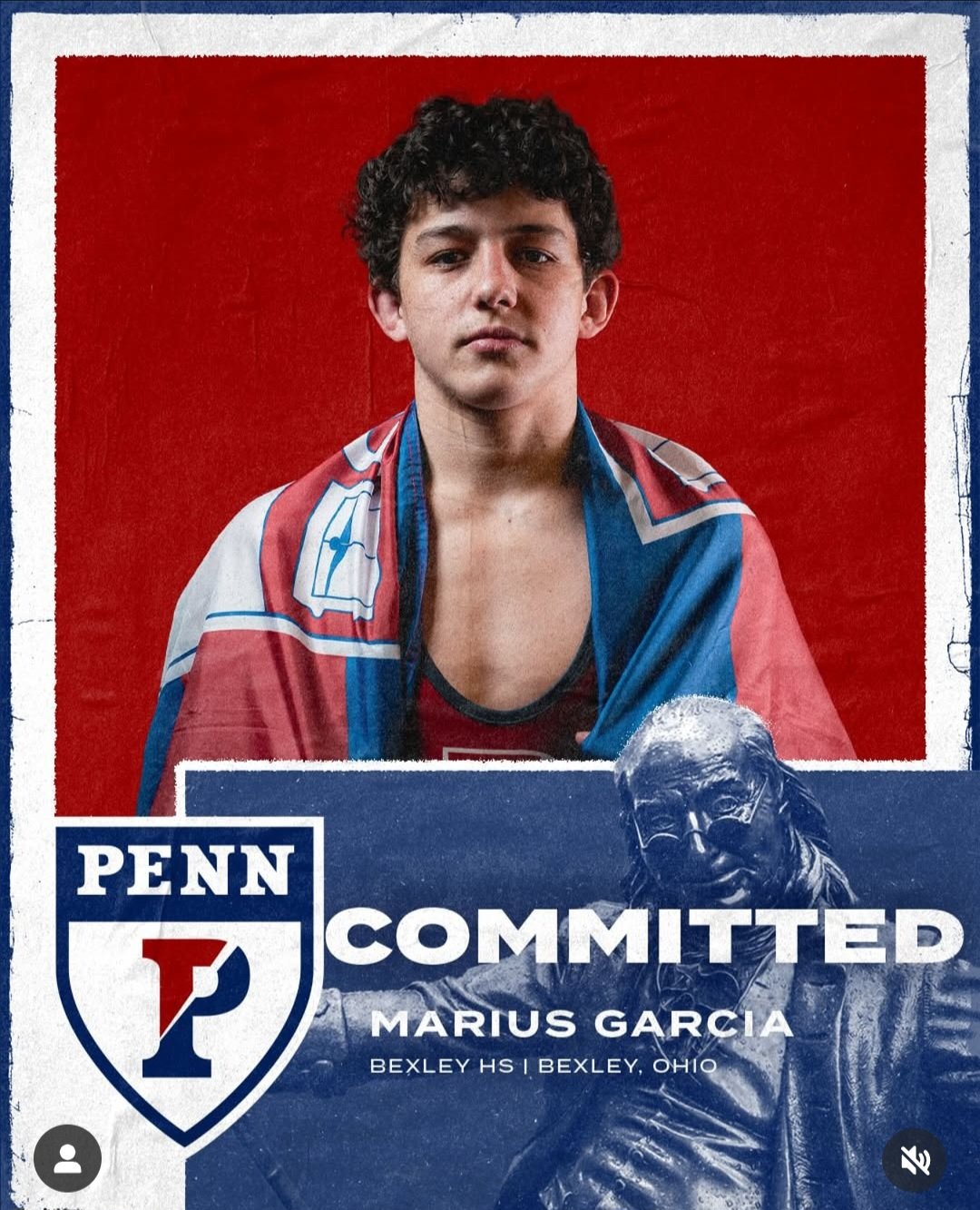

Marius Garcia

Bexley, Ohio

Class of 2025

Committed to Penn

Projected Weight: 125

Jack Baron

Germantown Academy, Pennsylvania

Class of 2026

Committed to Drexel

Projected Weight: 125

Recommended Posts

Create an account or sign in to comment

You need to be a member in order to leave a comment

Create an account

Sign up for a new account in our community. It's easy!

Register a new accountSign in

Already have an account? Sign in here.

Sign In Now