Interesting article on the right vs left argument

-

Latest Rankings

-

Updated

-

Updated

-

Updated

-

Updated

-

-

College Commitments

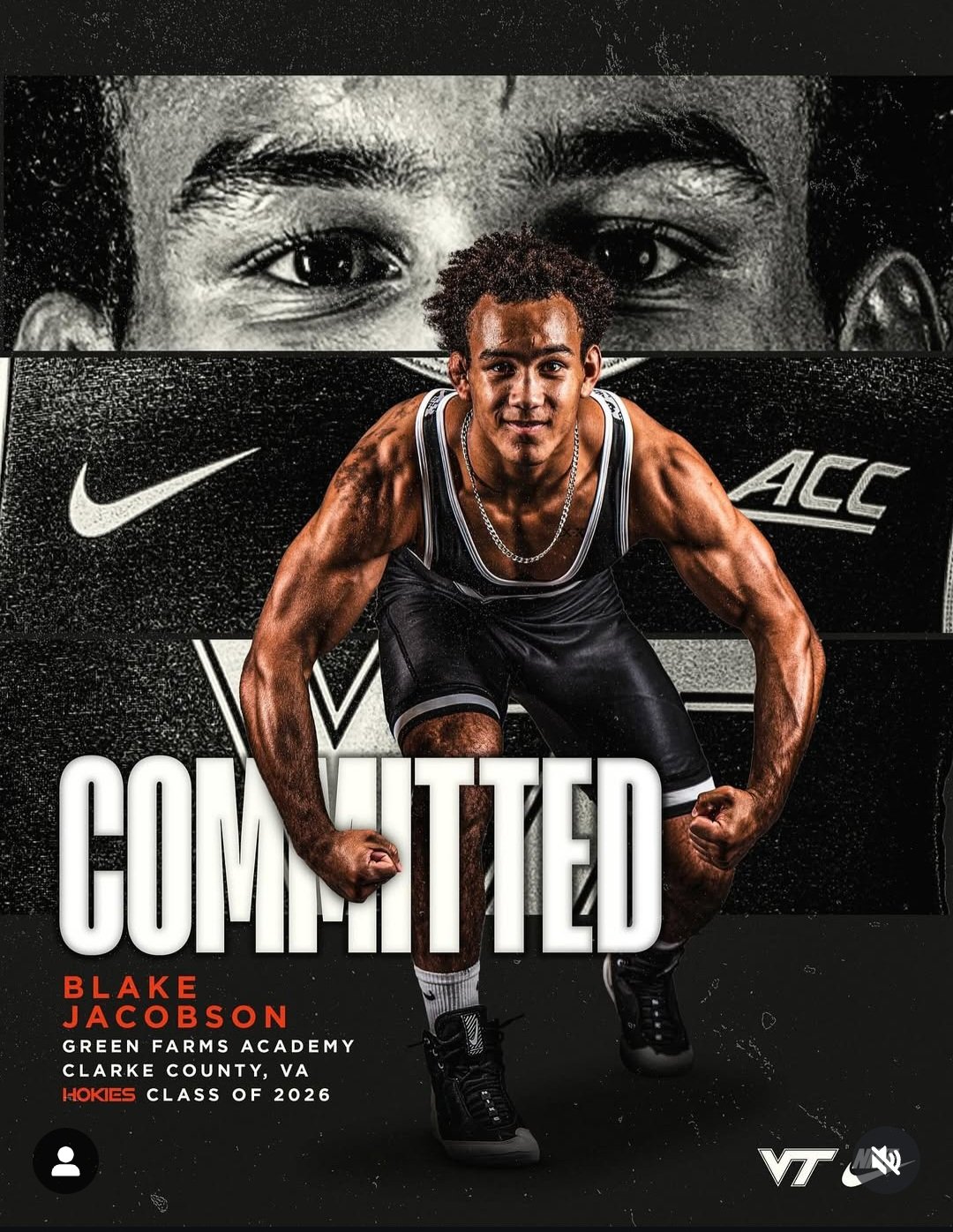

Blake Jacobson

Greens Farms Academy, Virginia

Class of 2026

Committed to Virginia Tech

Projected Weight: 174

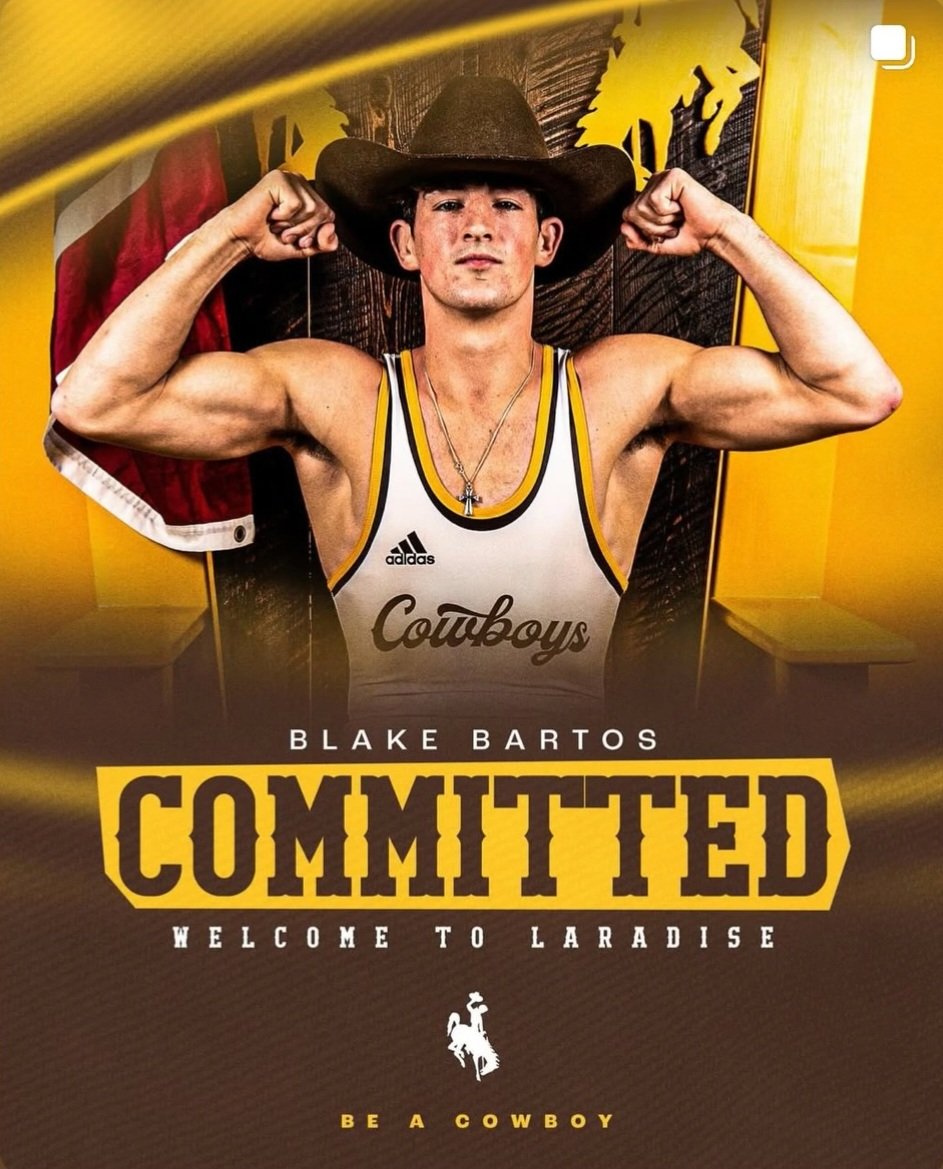

Blake Bartos

Medina Buckeye, Ohio

Class of 2026

Committed to Wyoming

Projected Weight: 141

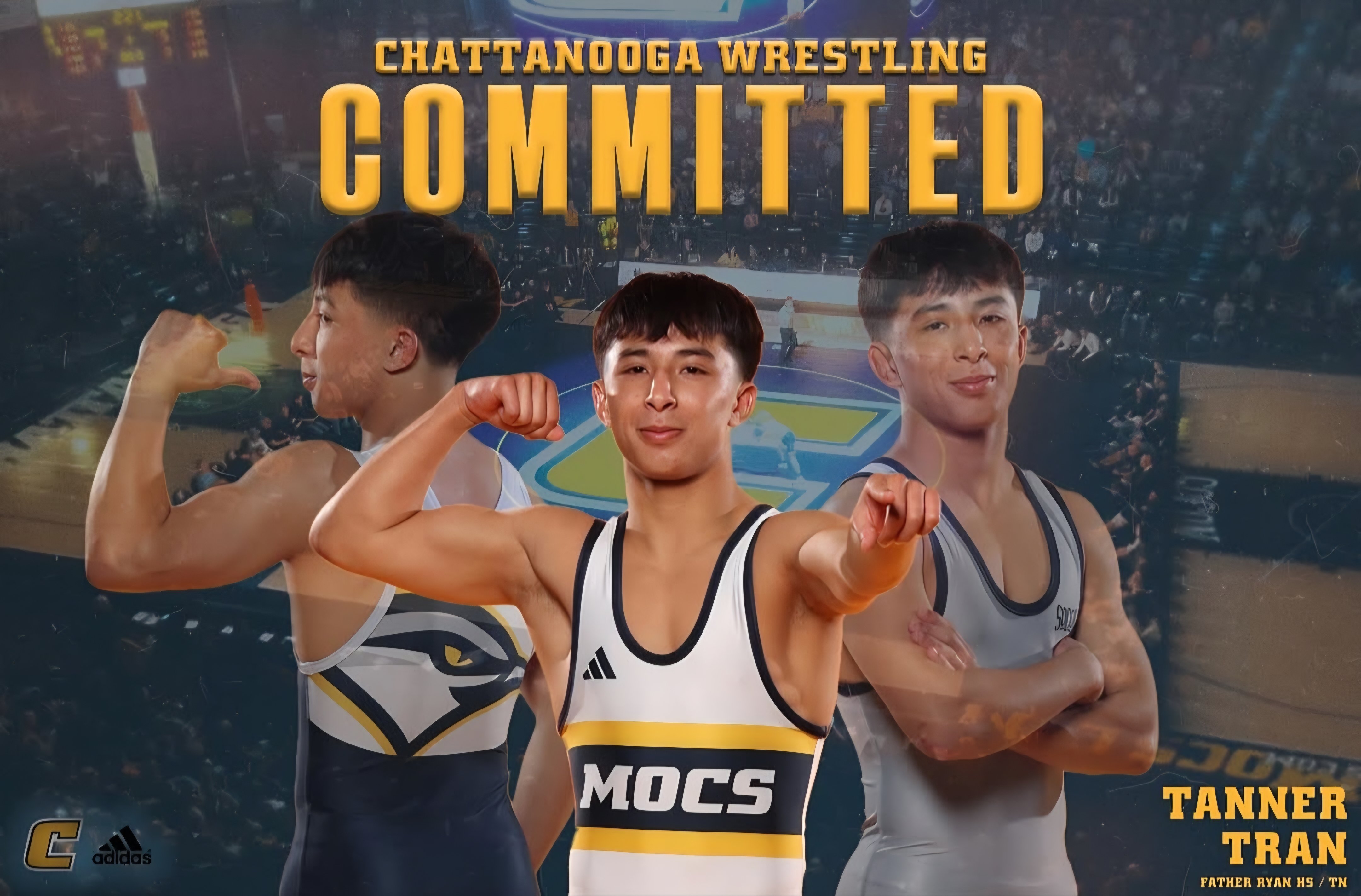

Tanner Tran

Father Ryan, Tennessee

Class of 2026

Committed to Chattanooga

Projected Weight: 125

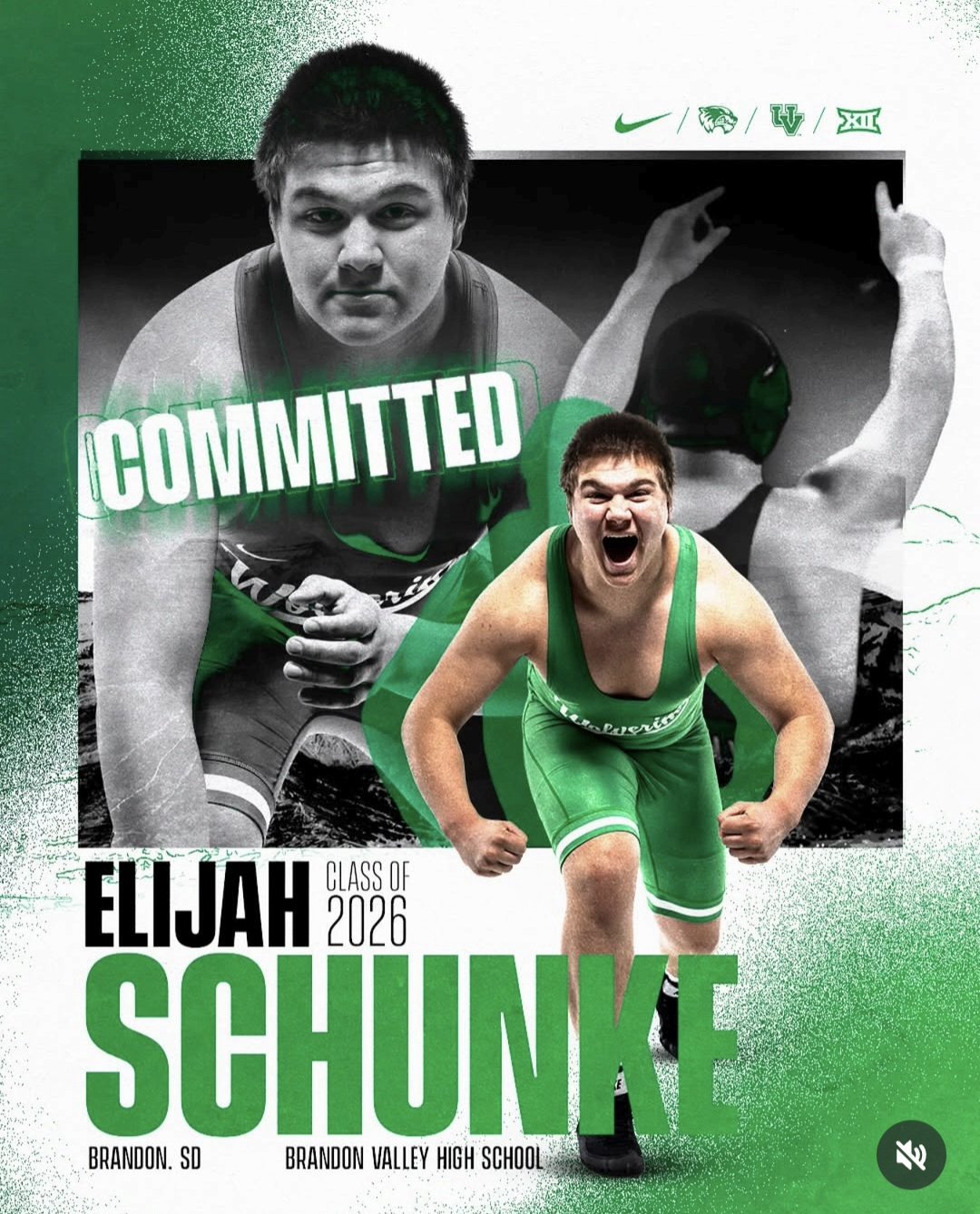

Elijah Schunke

Brandon Valley, South Dakota

Class of 2026

Committed to Utah Valley

Projected Weight: 285

Recommended Posts

Create an account or sign in to comment

You need to be a member in order to leave a comment

Create an account

Sign up for a new account in our community. It's easy!

Register a new accountSign in

Already have an account? Sign in here.

Sign In Now